"How do you do therapy?" Give a damn.

/Someone asked me, "How do you do therapy?" How do I do therapy? Wow. I mean it's a fair question. But how do you distill decades of study, experience, mentoring, and training into a brief answer that would actually convey anything? It's hard to quantify something that is both so quantifiable and qualitative at the same time; that has so much of science and research as well as art and intuition.

As an inexperienced substance abuse counselor in my first job in rehab, I desperately asked myself the same question, "How do I do therapy?!" My very first client was a hardened young construction worker spilling his guts to me about the horrifying abuse at the hands of his sadistic father. I had no clue how to do therapy then. One day the dam burst out of nowhere and this tough man broke down and sobbed with the exquisite and excruciating pent-up pain of years hidden behind his addictions. I felt sorry for this client who was stuck with this clueless counselor. I didn't know technique much then. I didn't know much of anything. I was straight out of my undergraduate program back when you didn't need a license to be a substance abuse counselor. The truth is I didn't have a clue. But you know what? I gave a damn. A big one. And he knew it. He felt it. And sadly only for the first time in his life, he felt someone truly, sincerely, deeply giving a damn about him—right there in my pathetic little run-down basement office with this novice wet-behind-the-ears counselor. And that is what mattered: compassion—just giving a real, sincere heart-felt damn. It worked. He trusted me because that unfeigned caring and willingness to just be with him in his pain with simple acceptance was enough.

But still, I asked that question for years. "How do you do therapy?" It's a great question. It's an important question. I worried that I'd screw up a person's life if I didn't know what I was doing—if I got it wrong if I didn't know the right answer, method, or strategy. But even in all the learning and not knowing I still had my ace in the sleeve—the one thing that I knew, that I always knew no matter who I worked with: I just gave a damn. Really.

And now all these years later I do know what I'm doing, and oh, man! it feels SO good to have the confidence that can only come from earning that hard-won knowledge, experience, and insight. What a difference that makes for myself and my clients! Now I've got tons of clues. I know the research. I have heaps, and tons and gobs of experience with this, that, whatever—you name it. And I love, love, love all of it. I love the models, the theories, the research, the books, the conferences, my colleagues. It is freaking amazing. I am never bored. Oh, and my clients. What they teach me! They fascinate me. They give me the rare gift of entering into the most private, sacred recesses of their lives. It humbles me. Wow... Wow. I love them. I admire them. I respect them so much.

And that's what most people have no clue about. They have no idea how amazing it is to be in a therapeutic relationship with another human being. Instead, they say, and I hear it all the time:

"Man, I couldn't do what you do—just listen to people complain and moan about their problems all day. It just sounds so depressing."

I reply, "Yeah, that does! I'm so glad I don't do that."

"What do you mean you don't do that?"

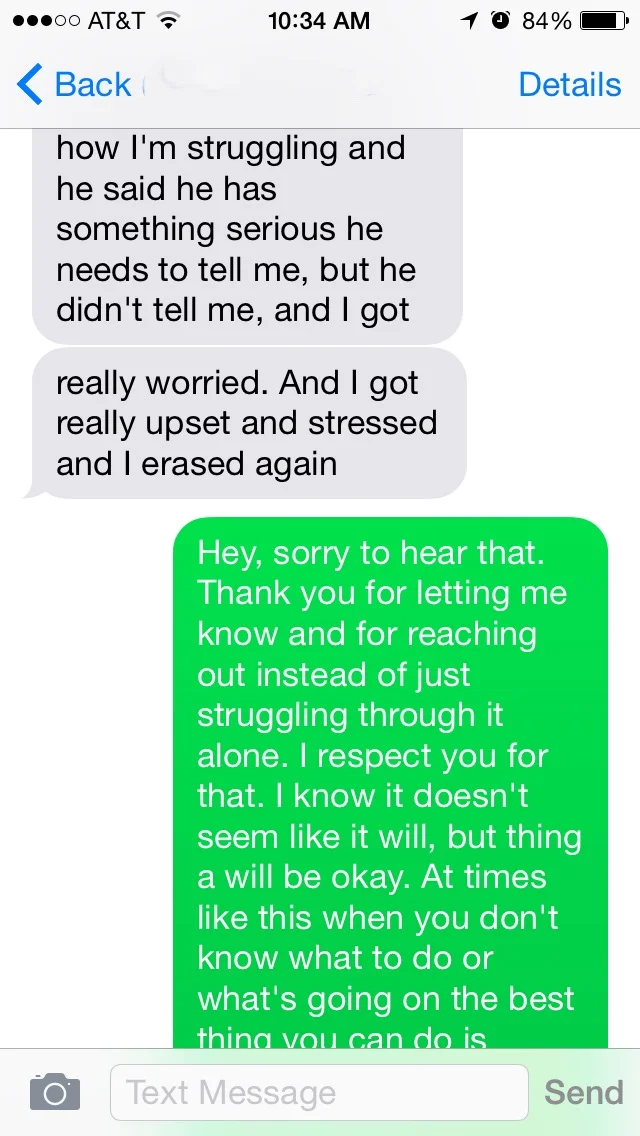

"Well, yeah, people have problems, but who doesn't? I mean welcome to life—if you've got a pulse and you happen to be human expect to get knocked around at some point on this planet. But the people who walk through my door day-in and day-out are the ones who are healthy and humble and smart enough to say, 'Hey, I've got a problem here. I'm stuck. I need help. Instead of sitting on my butt complaining and moaning, I think I'll get way out of my comfort zone, give this therapy gig a shot and do whatever it takes to make my life better.' We call that 'being proactive.' I mean, that takes some real guts to reach out to some stranger (a professional stranger, but still a stranger), open yourself up completely and face the things my clients tend to face. It isn't easy to change. Ever try changing? Yeah, it's tough, right? Well, these people are doing change to the 10th power and I find that wicked cool. And we sit in my office face-to-face and figure out the puzzle pieces, stare down the tough, tough stuff, come up with all kinds of fascinating solutions together, and we drill, practice, drill, practice, drill, practice until it finally clicks. Oh, and we laugh. A lot. So no, I don't do what you said I do: ‘deal with problems all day.’ No, instead my clients and I deal with solutions all day. And while at the end of my day, I may be mentally wiped, I'm also energized. And humbled. And grateful. And often when everyone's gone I can be seen fist-pumping the air: 'Yeah! We nailed it!'"

And the only reason we nailed it is because I earned their trust and they gave their trust—not because of my degrees on the wall, but simply and genuinely because I gave a damn.

Usually, my profession is made a joke. And really that doesn't bother me because it can be a funny profession, and if you know me I'm the last guy to take myself too seriously. So the jokes are fine. And trust me, I know a lot of therapists and therapies that I think are jokes—sad ones—so much so that I wouldn't send my worst enemy to them. Further, most media examples portray therapy with the over-worn cliches of some poor schmuck laying on the couch being asked "How does that make you feel?" and "Tell me about your mother." Rarely do I see the nobility of my profession adequately portrayed. Except, that is, in one example: The movie Good Will Hunting with Matt Damon and Robin Williams. Nailed it. Nailed it, nailed it, nailed it. Why? Because it was just the therapist being real and just simply giving a damn. Because he could see through the crap and into the REAL person inside—the person behind the past, behind the posturing, behind the defenses, behind the diagnosis, behind the clinical psychobabble mumbo jumbo.

Here's a clip to give you an example of what it looks like (spoiler if you haven't seen it yet) but the full movie is so much better to appreciate the full context of what's led up to this scene.

So the next time someone asks me, "How do you do therapy?" I'm just going to tell them, "Watch Good Will Hunting. It's something like that."